EAPM- Special Interest Group “Chronic Pain”

Mission Statement

The SIG of chronic pain will contribute in collaboration with the EAPM to increase the knowledge about psychosomatic components of chronic pain in this way:

- To stimulate multinational and multi-professional exchange between researchers and clinicians that are active on the field of chronic pain. The SIG will encourage this exchange inside the EAMP as well as with other medical and psychological associations. This includes to create connections between EAPM and Pain societies;

- To disseminate, between EAPM members, the evidences relative to the impact of psychological, psychopathological and neurobiological components on the perception and disability of pain;

- To organize symposia in the EAPM congresses – and also beyond – focusing on research activities and also on clinical and service developmental aspects;

- To stimulate the new generation to study chronic pain becoming a bridge for knowledge exchange between specialized centers in pain;

- To setup joint studies and to write or support articles and books in this field.

Researchers and clinicians could contribute to deepen knowledge on psychosomatic aspects of chronic pain.

(As of december 2020)

Chair: Antonella Ciaramella, Italy

Members:

Anne-Françoise Allaz, Switzerland

Ronald Burian, Germany

Amnon Mosek, Israel

Jonas Tesarz, Germany

Background:

Chronic pain is a condition involving body and mind. This concept was already contained in the 1994 Merskey & Bolund definition of pain, endorsed by the International association of study of pain (IASP), which was accepted globally by health care professionals and researchers in the pain field, governmental, and nongovernmental organizations, including the World Health Organization. This definition became the essence of the concept of pain: “Pain is an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage”.

Nevertheless, recently, a task force proposed by Judit Turner criticized this definition because it ignored the multiplicity of mind-body interactions, in a persisting Cartesian perspective. In particular, the present definition is thought to neglect the ethical dimensions of pain and not adequately address pain, not including for example the nonverbal behavior as can be found in the powerless and overlooked population such as the elderly and infants.

A revised IASP definition of pain was proposed in the 2020 (Raja et al., 2020): “Pain is an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with, or resembling that associated with, actual or potential tissue damage”.

Pain is a personal experience influenced by psychological, social and biological factors. Pain and nociception are two different phenomena. A subject learns his/her own concept of pain during his/her life experiences. Subjects with pain should be acknowledged and respected. Although pain usually serves an adaptive role, it can compromise psychological and quality of life well-being. The inability to communicate does not negate the possibility that human but also non-human animal experience pain.

As much as 31% of people in the USA (Johannes et al., 2010) and 19% in Europe (Breivik et al., 2006) have had pain in the last 6 months. Pain and its consequences represent one of the greatest costs for the health system as it is often the reason for repeated consultations or hospitalizations, as well as for work leave.

Pain is functional when it is warning for a heart attack or an infectious disease. However when it becomes chronic, it looses it alarm function. The warning system may become deregulated and evolve in “Pain sensitization”, representing a pain vulnerability and memory inscribed in a central nervous system plasticity, which is under emotional influences. Chronic pain becomes a leading source of human suffering and disability (Treed et al., 2019). Pain itself and many diseases associated with chronic pain are not immediately life threatening; people can continue to live on with their pain during their entire life.

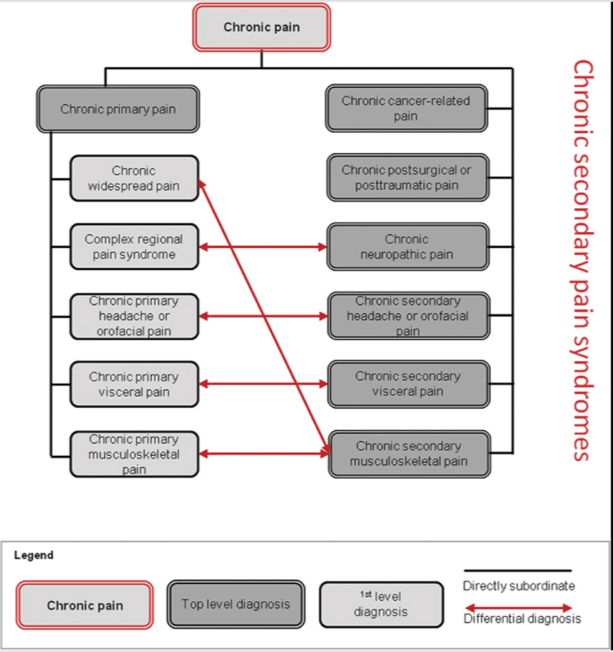

New Pain IASP/WHO classification distinguishing primary and secondary pain conditions for ICD-11

In “many modern health care systems, referral for specific treatment such as multimodal pain management is dependent on suitable ICD codes as indications” (Treed et al., 2019).

Indeed, a systematic classification of chronic pain was developed by a task force of the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) (Treed et al., 2015). This classification has been integrated with the existing pain diagnosis (e.g. International Headache Classification of the International Headache Society, ICHD, it has also been endorsed by WHO and will be included in ICD 11). This new classification is providing precise definitions and further characteristics features distinguishing chronic pain in primary and secondary pain syndromes, including the severity of pain, its temporal course and evidence for psychological and social factors.

Chronic primary pain is defined as “pain in one or more anatomical regions that persists or recurs for longer than 3 months and is associated with significant emotional distress or functional disability (interference with activities of daily life and participation in social roles) and that cannot be better accounted for by another chronic pain condition” (Nicolas et al., 2019). As reported in the ICHD the recognition of migraine as a primary headache disorder has been a crucial step. Similarly, conditions such as fibromyalgia or complex regional pain syndrome may qualify for classification as primary pain disorders.

Without diminishing the relevance of psychosocial factors in the perception of secondary chronic pain, the role of psychiatrists and psychologists and other mental health professionals in the management of primary pain is crucial.

The effort of our EAPM SIG “Chronic pain” is aimed at improving the etiopathogenetic knowledge of this form of pain as well as improving its management.

Secondary chronic pain, may be linked to osteoarthritis or diabetic polyneuropathy, where it may at least initially be considered as a symptom.

Both primary and secondary pain conditions are chronic since pain is a long-term condition requiring special treatment and care. Pain management should be guided by patient-reported severity and the distressing and disability conditions should be included as a code in the pain severity.

Figure 1 and its comments by Treede et al. summarises the new IASP/ICD11 classification of chronic pain (Reproduced from Treed et al., PAIN 2019; 160: 19-27).

Figure 1.:

Structure of the IASP Classification of Chronic Pain. In chronic primary pain syndromes (left), pain can be conceived as a disease, whereas in chronic secondary pain syndromes (right), pain initially manifests itself as a symptom of another disease such as breast cancer, a work accident, diabetic neuropathy, chronic caries, inflammatory bowel disease, or rheumatoid arthritis. Differential diagnosis between primary and secondary pain conditions may sometimes be challenging (arrows), but in either case, the patient’s pain needs special care when it is moderate or severe. After spontaneous healing or successful management of the underlying disease, chronic pain may sometimes continue and hence the chronic secondary pain diagnoses may remain and continue to guide treatment as well as health care statistics

Integration of pain within the new DSM V Somatic Symptom Disorder classification

Also complex is the diagnosis of “Somatic Symptom Disorder” (SSD, DSM-5) in the presence of chronic pain. The Pain classification of ICD 11 was developed in parallel to the SSD classification, therefore both classifications may be used by pain specialists.

The SSD DSM-5 diagnosis that replaced the former DSM IV “somatoform disorder” did not entirely eliminate the confusions and stigmatization attributed to pain not associated with a medical condition (Katz et al., 2015).

Nevertheless, the new classification of SSD in chronic pain patients will take into account the psychological and behavioral factors that characterize SSD such as sick role, alexithymia or somatosensory amplification. The latter factor seems important. For example, it has been associated with fibromyalgia more than with other chronic painful conditions (Ciaramella et al., 2020).

Psychopathological aspects of chronic pain

Among several other factors, the presence of psychopathology increases the perception of pain and disability associated to it (Cedraschi & Allaz, 2005). The prevalence of depression in chronic pain subjects is ranging from 30 to 60% increasing social cost, disability and suffering (Bair et al., 2008; Arnow et al., 2006). Chronic neuroinflammatory process seems to be one factor underlying this comorbidy inducing sickness responses (Walker et al., 2013). As Kroenke and collegues have mentioned, pain and depression are most common symptoms in primary care (Kroenke et al., 2009) with an increased prevalence in women (34.5% vs. 20.3% in males) as shown in a survey from Spain (Calvó-Perxas et al., 2016).

Anxiety is another psychopathological condition affecting chronic pain. For instance, in a recently described chronic low back sample the anxiety disorders co-occurred with a 35.8% prevalence where generalized anxiety disorders (GAD) was the most common (12.8%) (Kayhan et al., 2016). Other studies show a strong association of chronic pain with panic disorders (PD) and Post-traumatic stress disorders (PTSD) (McWilliams et al., 2003). Panic disorder comorbidity is really insidious since it could increase side effects due to neurovegetative dysfunction as is the case of ziconotide, an intrathecal treatment for neuropathic pain (Poli & Ciaramella, 2011). Agoraphobia when added with a lifetime depression increases disability. These two conditions often co-occur with a dysfunctional coping style in subjects with chronic low back pain (CLBP) (Ciaramella & Poli, 2015).

Furthermore, the presence of mild to moderate anxiety also influences perception and behavior of chronic pain through the involvment of entorinal cortex of the hippocampal formation (Ploghaus et al., 2001).

Whereas recent advances in neurosciences have underlined the importance of brain structures related to “negative” affects and emotions, developmental or epigenetic influences (Landa, 2012; Anis & Mosek, 2018) are also to be considered, as well as the importance of early traumatic experiences (Tesarz, 2018). The early diagnosis of a somatization disorder could predict the chronicity of pain by modifying cognition and facilitating the memory of pain in subjects who have experienced stressful or traumatic events (Ciaramella, 2018).

Moreover, present integrative models include personal history and vulnerabilities as well as cognitive factors, cultural aspects (Dreher et al, 2017)) and interpersonal dimensions as essential modulators of pain perception and disability (Allaz & Cedraschi, 2015).

Treatment approaches

Psychopharmacological treatment is commonly used in the management of pain. A large number of publications report that typical tricyclic antidepressant medications are successful in treating chronic pain (Dharmshaktu et al., 2012). Tricyclic antidepressants are effective in neuropathic pain as well in the rat model (Burke et al., 2015) as in the human clinical studies (Kalita et al., 2014) more when it is associated with depression. Several strong evidences showed that the SNRI are capable of providing relief from chronic pain whether directly associated with depression or not (Briley, 2004). The SSRI antidepressants are effective to control headache and fibromyalgia but few rigorous studies in chronic pain subjects elucidate the correlation of analgesia with the improvement of depression (Ciaramella et al., 2019; Banzi et al., 2015).

Besides psychopharmacological drugs as adjuvants to treat pain, multi modal therapies are indicated. Among them several mind-body techniques contribute widely to pain management Various psychotherapeutic approaches have shown their beneficial effects (Tesarz, 2018, Allaz, 2021). The role of pain acceptance is increasingly emphasized in cognitive or mindfulness based therapies (Dressel & Burian, 2019).

The benefits of biofeedback, mindfulness, movement therapies and relaxation based therapies in patients suffering from fibromyalgia have been investigated in the recent electronic searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (Theadom et al., 2015). In strong contrast to clinical experience, the quality of the evidence was very low or low due to the quality of available studies. Further research in this field is warranted.

The SIG Chronic pain

November 2020

References

Allaz AF. Douleurs et émotions. Intégrer les émotions dans le traitement de la douleur. [Pain and emotions]. Editions Vigot-Maloine, Paris, 2021. (in French)

Allaz AF et Cedraschi C.

Pain and emotions. In : Pickering and Gibson (Eds) : Pain, Emotions and Cognition : A complex nexus. Springer international Switzerland, 2015 : pp 21-34.

Anis S & Mosek A. [Epigenetic mechanisms in models of chronic pain- A target for novel therapy? ] Harefuah. 2018 Jun;157:370-373. (in Hebrew).

Arnow BA, Hunkeler EM, Blasey CM, Lee J, Constantino MJ, Fireman B, Kraemer HC, Dea R, Robinson R, Hayward C. Comorbid depression, chronic pain, and disability in primary care. Psychosom Med. 2006 Mar-Apr; 68(2):262-8.

Bair MJ, Wu J, Damush TM, Sutherland JM, Kroenke K. Association of depression and anxiety alone and in combination with chronic musculoskeletal pain in primary care patients. Psychosom Med. 2008. Oct; 70(8):890-7.

Banzi R, Cusi C, Randazzo C, Sterzi R, Tedesco D, Moja L. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) for the prevention of tension-type headache in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 May 1;5:CD011681. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011681.

Breivik H, Collett B, Ventafridda V, Cohen R, Gallacher D. Survey of chronic pain in Europe: prevalence, impact on daily life, and treatment. Eur J Pain. 2006 May;10(4):287-333. Epub 2005 Aug 10.

Briley M. Clinical experience with dual action antidepressants in different chronic pain syndromes. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2004 Oct;19 Suppl 1:S21-5. Review.

Burke NN, Finn DP, Roche M. Chronic administration of amitriptyline differentially alters neuropathic pain-related behaviour in the presence and absence of a depressive-like phenotype. Behav Brain Res. 2015 Feb 1;278:193-201. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2014.09.044. Epub 2014 Oct 6.

Calvó-Perxas L, Vilalta-Franch J, Turró-Garriga O, López-Pousa S, Garre-Olmo J. Gender differences in depression and pain: A two year follow-up study of the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe. J Affect Disord. 2016 Mar 15;193:157-64. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.12.034. Epub 2015 Dec 29.

Cedraschi C & Allaz AF. How to identify patients with a poor prognosis in daily clinical practice? In: Van Tulder M, Waddell G (Eds). Non-specific Low Back Pain. Best Practice & Research in Clinical Rheumatology 2005;19: 577-91.

Ciaramella A. Psychopharmacology of chronic pain. Handb Clin Neurol. 2019;165:317-337. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-64012-3.00019-8. PMID: 31727220 Review.

Ciaramella A & Poli P. Chronic Low Back Pain: Perception and Coping With Pain in the Presence of Psychiatric Comorbidity. J Nerv Ment Dis . 2015 Aug;203(8):632-40. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000340.

Ciaramella A. The Influence of Trauma on Autobiographical Memory in the Assessment of Somatoform Disorders According to DSM IV Criteria. Psychiatr Q. 2018 Dec;89(4):991-1005. doi: 10.1007/s11126-018-9597-0. DOI: 10.1007/s11126-018-9597-0

Ciaramella A, Silvestri S, Pozzolini V, Federici M, Carli G. A retrospective observational study comparing somatosensory amplification in fibromyalgia, chronic pain, psychiatric disorders and healthy subjects. Scand J Pain. 2020 Nov 2:/j/sjpain.ahead-of-print/sjpain-2020-0103/sjpain-2020-0103.xml. doi: 10.1515/sjpain-2020-0103. Online ahead of print.

Dharmshaktu P, Tayal V, Kalra BS. Efficacy of antidepressants as analgesics: a review. J Clin Pharmacol. 2012 Jan; 52(1):6-17.

Dharmshaktu P, Tayal V, Kalra BS. Efficacy of antidepressants as analgesics: a review. J Clin Pharmacol 2012; 52:6–17.

Dreßel S, Burian R. [Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for patients with chronic pain]. Neuro aktuell. 2019 Sept; 7 (10): 34-40. (in German).

Dreher A., Hahn E., Diefenbacher A., Nguyen MH., Böge K., Burian H., Dettling M., Burian R., Ta TMT. Cultural differences in symptom representation for depression and somatization measured by the PHQ between Vietnamese and German psychiatric outpatients. J Psychosom Research 2017; 102:71-77.

Johannes CB, Le TK, Zhou X, Johnston JA, Dworkin RH. The prevalence of chronic pain in United States adults: results of an Internet-based survey. J Pain. 2010 Nov;11(11):1230-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2010.07.002. Epub 2010 Aug 25.

Kalita J, Kohat AK, Misra UK, Bhoi SK. An open labeled randomized controlled trial of pregabalin versus amitriptyline in chronic low backache. J Neurol Sci. 2014 Jul 15;342(1-2):127-32. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2014.05.002. Epub 2014 May 10.

Kayhan F, Albayrak Gezer İ, Kayhan A, Kitiş S, Gölen M. Mood and anxiety disorders in patients with chronic low back and neck pain caused by disc herniation. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2016 Mar;20(1):19-23. doi: 10.3109/13651501.2015.1100314. Epub 2015 Nov 2.

Kroenke K, Bair MJ, Damush TM, Wu J, Hoke S, Sutherland J, Tu W. Optimized antidepressant therapy and pain self-management in primary care patients with depression and musculoskeletal pain: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009 May 27;301(20):2099-110. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.723.

Landa A, Peterson BS, Fallon BA. Somatoform pain : A developmental theory and translational research review. Psychosom Med 2012; 74: 717-27.

McWilliams LA, Cox BJ, Enns MW. Mood and anxiety disorders associated with chronic pain: an examination in a nationally representative sample. Pain. 2003 Nov;106(1-2):127-33.

Anis S & Mosek A. [Epigenetic mechanisms in models of chronic pain- A target for novel therapy? ] Harefuah. 2018 Jun;157:370-373. (Hebrew).

Ploghaus A, Narain C, Beckmann CF, Clare S, Bantick S, Wise R, Matthews PM, Rawlins JN, Tracey I. Exacerbation of pain by anxiety is associated with activity in a hippocampal network. J Neurosci. 2001 Dec 15;21(24):9896-903.

Poli P, Ciaramella A. Psychiatric predisposition to autonomic and abnormal perception side-effects of ziconotide: a case series study. Neuromodulation. 2011 May-Jun;14(3):219-24; discussion 224. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1403.2011.00334.x. Epub 2011 Mar 1.

Theadom A, Cropley M, Smith HE, Feigin VL, McPherson K. Mind and body therapy for fibromyalgia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Apr 9;4:CD001980. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001980.pub3.

Walker AK, Kavelaars A, Heijnen CJ, Dantzer R. Neuroinflammation and comorbidity of pain and depression. Pharmacol Rev. 2013 Dec 11;66(1):80-101. doi: 10.1124/pr.113.008144. Print 2014.

Merskey H and Bogduk N. Classification of chronic pain-descriptions of chronic pain syndromes and definitions of pain terms- Second edition. Seattle, IASP Press, 1994..

Raja SN, Carr DB, Milton Cohen M, Finnerup NB , Flor H, Gibson, Keefe FJ , Mogil JS , Ringkamp M, Sluka KA , Song XJ , Stevens B, Sullivan MD , Tutelman PR , Ushida T, Vader K. The revised International Association for the Study of Pain definition of pain: concepts, challenges, and compromises. Pain 2020 May 23. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001939.

Tesarz J, Gerhardt A, Eich W. [Influence of early childhood stress exposure and traumatic life events on pain perception]. Einfluss frühkindlicher Stresserfahrungen und traumatisierender Lebensereignisse auf das Schmerzempfinden Schmerz. 2018 Aug;32(4):243-249. (German).

Tesarz J. Psychosomatik in der Schmerztherapie. Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart, 2018.

Treede RD, Rief W, Barke A, Aziz Q, Bennett MI, Benoliel R, Cohen M, Evers S, Finnerup NB, First MB, Giamberardino MA, Kaasa S, Korwisi B, Kosek E, Lavandʼhomme P, Nicholas M, Perrot S, Scholz J, Schug S, Smith BH, Svensson P, Vlaeyen JWS, Wang SJ. Chronic pain as a symptom or a disease: the IASP Classification of Chronic Pain for the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11). Pain. 2019 Jan;160(1):19-27. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001384. PMID: 30586067 Review.

Treede RD, Rief W, Barke A, Aziz Q, Bennett MI, Benoliel R, Cohen M, Evers S, Finnerup NB, First MB, Giamberardino MA, Kaasa S, Kosek E, Lavand’homme P, Nicholas M, Perrot S, Scholz J, Schug S, Smith BH, Svensson P, Vlaeyen JW, Wang SJ. A classification of chronic pain for ICD-11. PAIN 2015;156:1003–7.

Nicholas M, Vlaeyen JWS, Rief W, Barke A, Aziz Q, Benoliel R, Cohen M, Evers S, Giamberardino MA, Göbel A, Korwisi B, Perrot S, Svensson P, Wang SJ, Treede RD. The IASP Taskforce for the Classification of Chronic pain. The IASP classification of chronic pain for ICD-11: chronic primary pain. PAIN 2019;160:28–37.